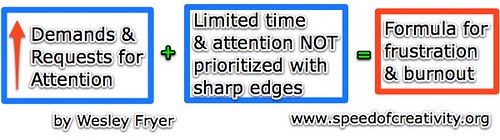

It is quite challenging to return to “normal life” and work after a week-long trip and face email inboxes.Since starting David Allen’s book “Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity” several months ago, I’ve started applying several of his core organizational principles with limited but positive results. Since it is quite hard to change long-established organizational and information-processing habits, I’m not overly frustrated at the slow pace of my success with his “GTD” strategies, but I am optimistic that I’m on a constructive road of more efficient behaviors.I was interested to read about David Allen and his new age roots in the article “The Guru of Getting Things Done” in the October 2007 edition of Wired magazine. (Which incidentally doesn’t appear to be online yet.) The article, in addition to providing surprising background about David’s past life and work, provides a succinct summary of Allen’s GTD philosophy as a single axiom and three basic rules. One of the key elements of GTD in the context of digital information processing is “inbox zero,” or an empty inbox. I continue to work toward this goal in both my personal and professional inboxes. Since getting an iPhone and connecting my personal Yahoo email account to it, keeping my personal inbox empty has become an achievable goal. Staying away (largely) from my email inboxes last week when we were in China led, of course, to a stack-up in emails, but I am hopeful to return to “inbox zero” early this week.Merlin Mann is another vocal advocate of the “inbox zero” philosophy. In July 2007 Merlin shared an hour-long “Google Talk” titled “inbox zero: action-based email” which gave him an opportunity to share his thoughts on this and other subjects related to organization and “getting things done.” Merlin is the founder of the 43 Folders website and this presentation was based on work Merlin has done in the past on this topic for 43 Folders:The slides Merlin used in his presentation are also available on SlideShare. His actual presentation is 32 minutes long, followed by about 30 minutes of Q&A.Like Merlin, my involvement with email started in earnest in the mid-1990s with a PINE email account. In 1988 at the US Air Force Academy, we had an internal email system, and I remember that someone in my 4 degree class got in trouble for accidentally emailing an unprofessional message about our commandant of cadets (a 1 star general) to the entire wing using wildcard characters— but other than that incident my memories of using email in the late 1980s and early 1990s are very limited. Email was sharply limited then in its inter-operaibility with other email systems, so its use was less widespread and it was inherently less powerful as a communication modality. That changed in the mid 1990s, and has certainly continued to morph as we enter the closing months of 2007. I never took a course or even a workshop on email management, yet being able to efficiently manage email has become a critical life skill for me and many others.Merlin contends that “one of the most important soft skills you can have in business today is being able to deal effectively with a high volume of email.” To do this, Merlin contends (as David Allen does) that you must be able to put in place a simple, effective system that allows you to have “a life outside of email.” Merlin suggests that an email system needs to “build walls” so people will NOT “live in their inbox.” Merlin defines knowledge workers as “people who add value to information,” and proclaims the sanctity of “edges” when it comes to dealing with all sorts of information, and in this presentation, email specifically.Merlin points out that there are NO BOUNDARIES inherent in the demands and requests which other people can put on your TIME and ATTENTION. He is absolutely right about this. In my last job at a university, I experienced this dramatically in the five years I worked as a support staff member for both faculty and staff. The lack of natural boundaries in the time and attention DEMANDS which others placed on my plate became, at times, quite overwhelming and almost debilitating. Thankfully, for much of my time at the university, I had excellent folks working with me on my team, and that was a great asset. The dynamics which I experienced are likely similar to those experienced by many others, and this can be a challenging situation to say the least. The key, according to Merlin, is making sure your time and attention are always “mapping” to the things you “claim are important.” Merlin acknowledges that many of his ideas around “inbox zero” come from David Allen and his GTD philosophy, which David calls “advanced common sense.”I heartily agree with Merlin that for those people who think every email needs a response, “that is 1993 talking.” He is SO right about that. Over-responding to email is a common problem, and leads to more problems in the form of more email!Merlin’s five “verbs” which he applies when processing email do sound like advanced common sense.” These are:

The key, according to Merlin, is making sure your time and attention are always “mapping” to the things you “claim are important.” Merlin acknowledges that many of his ideas around “inbox zero” come from David Allen and his GTD philosophy, which David calls “advanced common sense.”I heartily agree with Merlin that for those people who think every email needs a response, “that is 1993 talking.” He is SO right about that. Over-responding to email is a common problem, and leads to more problems in the form of more email!Merlin’s five “verbs” which he applies when processing email do sound like advanced common sense.” These are:

- delete (or archive)

- delegate

- respond

- defer

- do

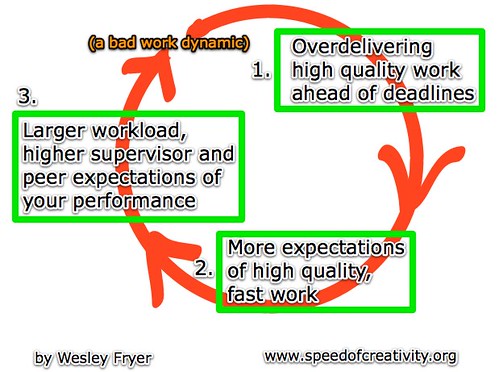

The key is getting into the mindset of converting email data into actions. Merlin uses the software OmniFocus to keep “ticklers” of things he has delegated and needs to follow-up on later.Merlin contends “your inbox should be for emails you haven’t read yet.” Simple, straightforward, but probably a concept many of us are not applying.”Liberate activities out of your inbox.” Merlin exhorts his audience to use a software application to serve as a task manager / task list.”If you keep your email box tidy, you will respect it more.” Merlin contends keeping your email box clean is a way of showing your own respect for your time and attention.Merlin summarizes “life hacking” as overriding the things the dumb part of your brain wants to do, and instead doing the things the smart part of your brain tells you to do.The key to all of this is regularly processing email according to a set of sharp edged rules. Merlin suggests turning off your email for periods of time while you go and work on something else. Merlin suggests scheduling “email dashes” when you check email on a periodic basis, maybe 10 minutes every hour. As much as you can, try to “shut off” email and then periodically check in with it.Merlin encourages us to periodically consider, throughout the day, whether or not we are spending our time and attention on things that map to our priorities. If there are ways we can make email “less noisy” and still remain productive, then we should do those things. We need to recognize the negative, disruptive function of email and limit or remove entirely its attention-demanding tyrannical nature from our daily lives. This dovetails nicely with thoughts I’ve written about previously relating to “digital discipline.”The dynamics of “access” to people, their ideas, and their attention have shifted with email, and Merlin addresses this in the Q&A time following his presentation. As he observes, email somehow conveys an idea to people that they have unlimited access to your time and attention. Where people would not likely call you after 9 pm on the phone to ask a question, they have no problem sending you an email about it. These are important issues to consider, and then decide how to “process” and handle with those “sharp edges” Merlin discussed earlier in the presentation.Managing people’s expectations of your response time to email is also important. Merlin relates his own history of learning how “over-delivering” in advance of deadlines can create negative feedback loops. I resonate with this as well. It’s as if being highly responsive and highly skilled creates a negative feedback loop of ever-increasing expectations for ridiculously short time suspense responses that require an enormous quantity and quality of work. That feedback loop is not sustainable for knowledge workers. Here is my attempt at a visual of this dynamic: Having boundaries with sharp edges is an essential skill. Perhaps this has always been true, but the near-ubiquitous access many knowledge workers now enjoy (?) or experience has likely multiplied the importance of this skill in the last ten years. I am writing about these ideas not because I have mastered them or found a “solution” to all these issues, but because I am actively working on them and seeking solutions.I think both David Allen and Merlin Mann have a lot to offer in the elusive quest for “inbox zero” and the larger goal of living a life characterized by peaceful effectiveness, despite the chaotic cauldron of information and attention demands which is constantly storming the gates of individual consciousness.Technorati Tags:merlinmann, attention, email, inbox, gtd, davidallen, gettingthingsdone, organization, overload

Having boundaries with sharp edges is an essential skill. Perhaps this has always been true, but the near-ubiquitous access many knowledge workers now enjoy (?) or experience has likely multiplied the importance of this skill in the last ten years. I am writing about these ideas not because I have mastered them or found a “solution” to all these issues, but because I am actively working on them and seeking solutions.I think both David Allen and Merlin Mann have a lot to offer in the elusive quest for “inbox zero” and the larger goal of living a life characterized by peaceful effectiveness, despite the chaotic cauldron of information and attention demands which is constantly storming the gates of individual consciousness.Technorati Tags:merlinmann, attention, email, inbox, gtd, davidallen, gettingthingsdone, organization, overload

Comments

2 responses to “Seeking the elusive “inbox zero””

I’ve been on GTD for the past year or so. It’s been a slow road, but a productive one. I’m currently one of the OmniFocus beta testers (having used KinklessGTD for some time). I actually discovered David Allen through 43 Folders! I’ve probably managed to reach a zero inbox about once every other month and it truly is a wonderful feeling!

Another change that has helped:

1. Open my Documents folder and you find 27 folders: A-Z and Someday.

2. The same structure of folders under my Inbox.

3. The same in my file cabinet.

All of this translates to no time thinking of where to file things.

And here’s one last tip from Merlin: Turn off all email notifications, phone and computer. Check email on your own time.

Your cycle of productivity really resonated with me. I have stepped out of the classroom this year to study and found near the end of my teaching time that I was facing severe burn out. The problem was that I am VERY good at my job and highly efficient. Therefore the demands put on me were at least twice as much as my colleagues faced. I completed every task on time or earlier with highly polished results. I am now very resentful and wondering how to start over. If I start working to the same time frame as everyone else I will seem as though I am ‘slack’ or not ‘pulling my weight’. How can you go back? How can you make things more manageable without people thinking that you are not working hard enough.

It is a really tricky situation to find yourself in. My year out of the classroom saved me and I have vowed never to get into the same situation again.