It’s amazing to realize how dramatically and quickly life has changed in many parts of these United States. Consider the following paragraph from Timothy Egan’s fantastic book, “The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl,” on pages 41-42:

In the fall of 1922, Hazel saddled up Pecos and rode off to a one-room, wood-frame building sitting alone in the grassland: the school-house. It was Hazel’s first job. She had to be there before the bell rang– five-and-a-half miles by horseback each way– to haul in drinking water from the well, to sweep dirt from the floor, and shoo hornets and flies from inside. The school had thirty-nine students in eight grades, and the person who had to teach them all, Hazel Lucas, was seventeen years old. In its first years, the schoolhouse lacked desks. Fruit crates, or planks nailed to stumps, did the job. After school, Hazel had to do the janitor work and get the next day’s kindling– dry weeds or sun-toasted cow manure.

Not only have we come a long way with our schools and the roles played by teachers since those frontier days on the prairie, we’ve also come light years with communications and NEWS. Egan continues on page 42:

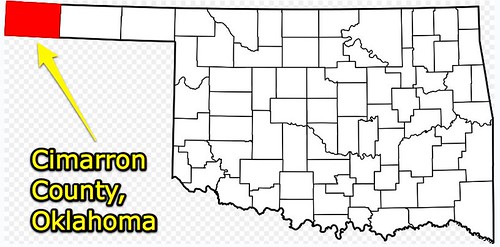

All the while, she wondered about a life far away, in one of the bustling cities of the Midwest, or just a place where the routine of a day was not so full of random death. The Kansas City Star arrived by mail in Boise City once a week, and Hazel got a sense of how fast America was moving: flappers, gangsters, and stunts– two men tried to play airborne tennis while standing, strapped, to the wings of a biplane. In Cimarron County, most people didn’t even have electricity, and many still lived in earthen dugouts or soddies.

These paragraphs are from chapter two of Egan’s book, “No Man’s Land,” and reveal a history which I’ve heard in snippets but never experienced in a full, narrative style. If life was moving “fast” in the 1920s in “midwest cities” relative to the Oklahoma panhandle, what could we say about the pace of change today in 2009?!

Before reading Egan’s book, I didn’t realize “No Man’s Land” (the Oklahoma panhandle) was cut off from Texas in 1845 by the Missouri Compromise, which prohibited slave states from entering the union which included land north of the 36.5 degree latitude line.

I also didn’t realize how incredibly lucrative dry-land wheat farming was during the war years of 1914 – 1919 and before the dust bowl hit, when “multimillionaire public servant…Herbert Hoover” was the wartime food administrator guaranteeing the price of wheat at $2 per bushel. It had sold just years before at 80¢ per bushel. Egan writes on page 44:

For a young family casting about for a way to make good money out of nearly nothing to start, the dryland wheat game looked like an easy gamble. Indeed. The self-described wheat queen of Kansas, Ida Watkins, told everyone she made a profit of $75,000 on her two thousand acres of bony soil in 1926– bigger than the salary of any baseball player but Babe Ruth, more money than the president of the Unted States made.

Interestingly, there is not a current English Wikipedia article for “Ida Watkins.”

Also of related interest, Egan’s entire book appears to be available as a “preview” in the scanned, free version available on Google Book Search. Apparently Egan’s publisher participates in Google Book Search’s “Partner Program.” It’s good to know the book is available free online, but I’m still glad to have the print version to curl up with at night. 🙂

We’ve only begun to document and share the stories of our state and our people on Celebrate Oklahoma Voices. Of the 228 educator and student-created videos published to our website as of this writing, I’m aware of only three which touch on dust bowl topics and themes.

Jeanette Hale’s video, “The Dirty Thirties,” is one of my favorites and shares stories from her aunt who lived through the dust bowl in the Oklahoma panhandle.

Find more videos like this on Celebrate Oklahoma Voices!

Deb Ever’s video “Woody Guthrie” shares a brief glimpse of Woody’s life and mentions how he was the “Dust Bowl Troubadour” documenting the lives and struggles of Oklahomans in the 1930s.

Find more videos like this on Celebrate Oklahoma Voices!

Scott Charlson’s video, “Sketches,” shares a poignant family story about Woody Guthrie, who certainly was one of the best known Oklahomans as a folk singer and vocal documentarian of everyday working life.

Find more videos like this on Celebrate Oklahoma Voices!

It is kind of amazing we don’t have more stories of Oklahomans’ experiences during the dust bowl and the Great Depression in our COV video library yet. We need to get serious about documenting these stories with audio and video! I’m reminded of an interview I shared as a podcast with Oklahoma Superintendent Doug Taylor back in September of 2008, along with the video Doug created in February 2008 when he participated in a Celebrate Oklahoma Voices workshop at the University of Central Oklahoma. Doug is the superintendent of Gage Public Schools, in extreme western Oklahoma. This was his first COV video:

Find more videos like this on Celebrate Oklahoma Voices!

Doug talked in his video about his desire to involve students in Gage Public Schools in a documentary effort to preserve the voices of those who lived through the dust bowl and the Great Depression. We’re scheduled to present a COV workshop in Buffalo, Oklahoma, in early August this year, which will be the furthest west we’ve been to date with the workshop. Jeanette Hale, who created the video “The Dirty Thirties,” lives in Lindsey, Oklahoma (in central Oklahoma) but grew up in the panhandle, in Guymon. We need to empower more Oklahoma educators and students from and in the panhandle to become digital witnesses!

Technorati Tags:

history, oklahoma, video, dust, bowl, thirties, panhandle, timothy, egan