Tremendous benefits await those who generously share their ideas with others. Leaders should not shy away from the challenges of developing professional expertise in multiple domains. Regular collaboration and networking over excellent food and drink can prepare the mind as a fertile field for the cultivation of life-changing thoughts. New technologies can present novel opportunities for invention as well as insight. Ideas matter. Leisure time is required to innovate. Coffeehouse culture can transform minds and society. These are some of the lessons I’ve gleaned from the life of Joseph Priestly, after reading Steven Johnson’s (@stevenbjohnson) excellent book, “The Invention of Air: A Story Of Science, Faith, Revolution, And The Birth Of America.” In this post, I’ll elaborate on these themes and attempt to persuade you that this book, as well as more specific study of the works of Joseph Priestly, are worth your time as a learner and a citizen.

Excited to find a signed 1st edition of @stevenbjohnson's "The Invention of Air" https://t.co/NTTCfT9m0J pic.twitter.com/ZJxQS5nbdq

— Wesley Fryer, Ph.D. ??? wesfryer.com/after (@wfryer) December 28, 2016

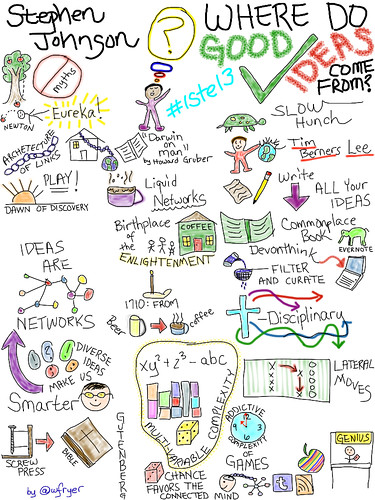

Steven Johnson (@stevenbjohnson) is one of my favorite authors. His book, “Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation,” is one of my all-time favorites.

Videos by and using the words of Steven feature prominently in my resources page for “Discovering Useful Ideas,” one of the breakout sessions I’m likely to share if you invite me to keynote your conference. The PBS series he developed and narrated, “How We Got To Now,” is also an all-time favorite and would be excellent to include in course materials focusing on innovation, invention and creativity.

In “The Invention of Air,” Johnson shares a delightful web of interconnected stories involving Joseph Priestly, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and a cast of other characters involved in the scientific as well as political developments of the late 1700s and early 1800s in England, The United States, and France. In this book, Johnson provided me with the most detailed account of the scientific work of Benjamin Franklin which I’ve read to date. Franklin, a member of “The Club of Honest Whigs,” was among those who encouraged and collaborated with Priestly in his varied scientific inquiries and discoveries. Priestly, in his well-read 1767 book, “The History and Present State of Electricity, with Original Experiments,” detailed Franklin’s now-famous “Kite experiment.” This publication contemporaneously elevated Franklin as an accomplished scientist into the consciousness of early America, and ripples down through the decades to us as a common tale schoolchildren learn about our nation’s founding fathers.

Open Digital Sharing

One of the things I admire most about Joseph Priestly is the generous way in which he shared his ideas. One of my “slow hunches” with my wife is “The Digital Sharing Project” (@digishare) which we eventually hope will become a regional, face-to-face conference. I’m so inspired by the creative sharing with reckless abandon modeled by the DS106 community and the DS106 Daily Create (@ds106dc).

#tdc1894 #ds106 #dailycreate Bad Dog on the Run … @ronald_2008 @cogdog pic.twitter.com/hHe5LWVXbV

— KevinHodgson (@dogtrax) March 16, 2017

Johnson credits Larry Lessig (@lessig) as his source for an opening quotation of the book by Thomas Jefferson, which summarizes well the views of both Jefferson and Priestly on idea sharing:

That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation.

The opportunities we have for digitally sharing our ideas across space and time in 2017 are unprecedented in human history. As an early adopter of “web 2.0 technologies” or the read/write web in the early 2000s, I’ve been a vocal advocate for generous digital sharing for almost 15 years now. As the Internet and the world-wide web have matured, however, we’ve seen troubling developments on the fronts of privacy and state surveillance which should concern all of us on spaceship earth, regardless of our national citizenship. I read, in the stories of Joseph Priestly in “The Invention of Air,” a call to citizen advocacy to not accept the political status quo as it is but instead, advocate for a better tomorrow shaped by the light of reason as well as collective action. This advocacy needs to extend into the realm of our modern surveillance state.

The recent article by Tim Berner’s Lee (@timberners_lee), “I invented the web. Here are three things we need to change to save it,” highlights 3 specific issues we need to collectively address in our digital information landscape of 2017:

- We’ve lost control of our personal data

- It’s too easy for misinformation to spread on the web

- Political advertising online needs transparency and understanding

I invented the web. Here are three things we need to change to save it https://t.co/Bv1hCjcyE2 by @timberners_lee @guardian via @nuzzel

— Wesley Fryer, Ph.D. ??? wesfryer.com/after (@wfryer) March 12, 2017

Tim’s ongoing work with The World Wide Web Foundation (@webfoundation) is important to follow and support on these topics.

These issues connect to Priestly and “The Invention of Air” because open digital sharing offers huge benefits to us as individuals and as a society, but is under threat by corporations, governments, and groups who want to exploit our data for agendas we may not support, understand, or even be aware of.

What a dream our interconnected world of online news, Twitter channels, and personal publishing would have been to Franklin, Priestly, Jefferson and others in the late 1700s! When Priestly was forced to immigrate to the United States after the riots he catalyzed in Birmingham, England, in 1791, he was significantly challenged by the slow pace of information flow between his home in rural Pennsylvania and larger cities of America, not to mention Europe. Johnston wrote in “The Invention of Air,”

Joseph grumbled about the effect the sluggishness of the postal system was having on his work. In London, Birmingham, and Leeds, information had traveled on the scale of hours or days. Communicating with the Honest Whigs or the Lunar Society via mail back home had been a conversational experience: you could make plans, or banter, jot off quick observations, swap half-formed ideas, at that accelerated rhythm. But the lag time just between Northumberland and Philadelphia was often a matter of weeks, and sending a message all the way to London took an entire season at least. This meant a detachment from world news as much as it did from personal connection.”

Our “new normal” of connected learning has matured around us swiftly since the start of the world-wide web in the 1990s. Reading about the powerful and positive exchanges of ideas which fueled Priestly’s work in science and other disciplines, I’m inspired to continue advocating for open digital sharing both online and through face-to-face gatherings.

LOVE this @creativecommons video! This is our mission too: "When we share, everyone wins" https://t.co/m3tpebxtNN

— Digital Sharing (@digishare) January 7, 2017

Multi-Disciplinary Expertise

Before reading “The Invention of Air” I had never heard of Joseph Priestly, or if I’d read his name, it hadn’t stuck in my mind. Steven Johnson has cognitively marked my consciousness with Priestly’s name now, however, and the variety of disciplines in which he wrote, published, and was regarded as a contemporary expert plays a major part in this. In addition to his array of “qualitative” scientific experiments which distinguished him in the scientific communities of England, France and the United States, Priestly was also a prolific and controversial author on faith and religion. Priestly was one of the founders of Unitarianism, a denomination which I have had limited exposure to and understanding of. Johnson highlighted Priestly’s book, “A History of the Corruptions of Christianity” (available as a free electronic download from archive.org) as the most significant theological influence on the faith and beliefs of Thomas Jefferson. I knew that the Jefferson Bible was a remix of the traditional books of the Bible by Thomas Jefferson, with all references to miracles and supernatural events (Jesus’ virgin birth, Jesus’ resurrection from the dead) removed, but I did not know what had primarily influenced Jefferson’s deist beliefs. My collision with the theological ideas of Joseph Priestly, thanks to “The Invention of Air,” is significant in at least two ways.

First of all, I continue to be fascinated by the tendency, which perhaps started with “The Age of Enlightenment,” for many people to view the advance of science as causally connected to the demise of faith and belief in God as well as organized religion. My own studies and understanding of science and the complexities of the universe have deepened rather than lessened my own faith, but this is certainly not a universal tendency. In the spirit of empiricism, as human beings armed with the scientific method have devised more names and explanations for objects and processes in our natural world, superstitions and mystical explanations for the ways of the world seem to diminish. I am thankful to Johnson for introducing me to Priestly, his influential theological writings, and the powerful influence they exerted on Thomas Jefferson as well as others.

Secondly, I find it personally inspiring to learn about Priestly’s advocacy and publishing history in diverse fields. One of Steven Johnson’s main points in “The Invention of Air” is that U.S. citizens should understand and embrace the historical heritage which our early leaders provided as experts in science as well as politics. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson are two of our founding fathers who fit this mould, and as Johnson notes, they didn’t just engage in scientific inquiry as an infrequent hobby like checkers, chess or bowling. Johnson wrote:

In the popular folklore of American history, there is a sense in which the founders’ various achievements in natural philosophy – Franklin’s electrical experiments, Jefferson’s botany – serve as a kind of sanctified extracurricular activity. They were statesmen and political visionaries who just happened to be hobbyists in science, albeit amazingly successful ones. Their great passions were liberty and freedom and democracy: the experiments were a side project. But the Priestly view suggests that the story has it backward. Yes, they were hobbyists and amateurs at natural philosophy, but so were all the great minds of Enlightenment-era science. What they shared was a fundamental belief that the world could change – that it could improve – if the light of reason was allowed to shine upon it.

These, then, are conjoined gifts of insight which Johnson shares in “The Invention of Air.” While the pursuit of science has become a highly specialized and quantified discipline, like Priestly and his contemporaries we can “refuse to compartmentalize science, faith, and politics.” We are not well served by politicians who avoid addressing the important scientific questions of our age. Rejecting the consensus of climate change scientists or discounting the evolutionary development of species on our planet remain politically popular among some voters but are certainly not scientifically informed views. We need leaders who, like some of our founding leaders in the United States, embraced both scientific inquiry as well as politics and statecraft.

"I wish I could just scream & let everybody know how big this is!"- extraordinary ice melt on #Greenland -Mike MacFerrin @CUBoulder #climate pic.twitter.com/hfZku8EHtA

— MoreThanScientists (@MTScientists) February 20, 2017

Johnson’s story of Priestly’s life and connected advocacy in science, faith and politics also inspires me in my own writing and publication aspirations. To date, the vast majority of my own books and other publications have been within the realm of educational technology and multimedia. While I have a specific list of book updates and new books I want to write within this genre, I also continue to be drawn to write, publish and advocate in a theological arena via the “Digital Witness for Jesus Christ” project. Learning about the advocacy and publishing career of Joseph Priestly inspires me in this regard. Although my own theological beliefs are not deist nor unitarian, I find in Johnson’s story of Priestly’s life encouragement for my own journey of faith, identity, advocacy, and life purpose.

#dw4jc “Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.”

Romans 12:12 NIVhttps://t.co/M88g1Hjdf5 pic.twitter.com/3wpP8nL3HE— Pocket Share Jesus (@PocketShare) March 3, 2017

Narrated Sermon #sketchnote on Luke 7:18-23 https://t.co/xxA8AArPCA @fpcedmond #fpcedmond #dw4jc #Jesus

— Pocket Share Jesus (@PocketShare) March 6, 2017

Slides for my Oct 27, 2016 chapel talk at school "Pocket Share Jesus with Bible Verse Infopics" are available https://t.co/BIRLIQXnEH #dw4jc pic.twitter.com/1m5GYE0yq7

— Pocket Share Jesus (@PocketShare) October 27, 2016

#dw4jc "…every Christian’s life is marked by windows of opportunity…” by @chipingram https://t.co/kyy9COBeh7 pic.twitter.com/dheT31BAM1

— Pocket Share Jesus (@PocketShare) March 6, 2017

Invest in Coffeehouse Initiatives

A final lesson which I gleaned from Steven Johnson’s book, “The Invention of Air,” is encouragement to continue investing in “coffeehouse initiatives.” In the book, Johnson details how motivating and transformative the coffeehouse gatherings of “The Club of Honest Whigs” were for Joseph Priestly, Benjamin Franklin, and many others. Breaking bread, indulging in some good beverages, and talking about issues and LEARNING together with others who share similar interests is a perennial recipe for cognitive dynamite.

There is tremendous power in online sharing and idea collaboration, but there is also fantastic energy when passionate people gather together to talk, learn, and break bread together over topics of shared interest. Some of the most professionally powerful experiences of my life as an educator have been face-to-face meetups with other passionate teachers: the Apple Distinguished Educator Institute in 2005, the Google Teacher’s Academy in Denver in 2009, and Unplug’d in 2012 in Ontario.

For the past five years, I’ve been blessed to collaborate with a wonderful group of passionate Oklahoma educators who have combined forces to put on the EdCampOKC professional development event. (@edcampOKC) I’ve also been able to encourage and support other individuals and groups who have been interested in hosting EdCamp events in other places in Oklahoma. (www.edcampok.org)

Our 2017 #EdCampOKC organizer team! In "Chillbo Baggins" style! #oklaed pic.twitter.com/df23NGZOJz

— EdCamp OKC (@EdCampOKC) March 4, 2017

As I continue to get older, I’m becoming more focused on investing my time, talents and resources in activities and experiences which I know are intrinsically GOOD. I put reading and discussing the Bible in this category, and I also put educator gatherings like EdCamps and PlayDates. My wife and I have been working on another “slow hunch” which relates to all these ideas, which we have formatively called “The Education Think Tank Potluck Club.” The website I’ve started (ettpc.org/about) is literally half-baked, but I’m sharing it now because Johnson’s narrative in “The Invention of Air” encourages me that we’re on the right track with this. None of these initiatives or ideas which are works in progress: Design – Create – Share, iPad Media Camp, The Digital Sharing Project, or #dw4jc are fully formed or in final form. They all connect to ideas, values, and experiences which I know are important and can be potentially transformative… and those are the reasons I continue to invest my heartbeats in them.

The almost weekly “EdTech Situation Room” (@edtechSR) webshows and podcasts which I co-host on Wednesday evenings with Jason Neiffer (@techsavvyteach – and frequently special guests) is a virtual “coffeehouse conversation on educational technology” which I’ve enjoyed immensely in the past year. It’s not only provided we with opportunities to exchange thoughts about #EdTech news and issues, but also delve much deeper into privacy issues and concerns raised by state and corporate sponsored surveillance.

Ep 43: @mguhlin & @wfryer talk @SXSWedu, iBooks, iBooks Author, #DigCit, #Privacy, @wikileaks #Vault7, #surveillance https://t.co/krDUqhZWuo pic.twitter.com/pHVgjOtGho

— EdTech Situation Room @edtechsr@mastodon.education (@edtechsr) March 9, 2017

Steven Johnson’s tales of Joseph Priestly in “The Invention of Air” spurs me on to continue sharing, collaborating, and working with others to remake our world into a better version of itself. His tales inspire me to remain a passionate and dedicated idealist, and that is encouragement I both need and appreciate.

There’s more I could share, but I’m sure I’ve included more than I needed to in this reflective post. Check out “The Invention of Air” as well as the other books Steven Johnson has written. And if you find this post helpful or inspiring, please let me know via a comment below or by reaching out on Twitter to @wfryer.

Here’s to many more coffeehouse collaborations in your life and in mine!

"…most important ideas enter the pantheon because they circulate" by @stevenbjohnson cc @digishare #edtechSR pic.twitter.com/w3SbFKvF3Y

— Wesley Fryer, Ph.D. ??? wesfryer.com/after (@wfryer) March 14, 2017

"…most of the great inventors were blessed with something else: leisure time" by @stevenbjohnson pic.twitter.com/n5x2orQnEC

— Wesley Fryer, Ph.D. ??? wesfryer.com/after (@wfryer) March 14, 2017

"Humans made the steam engine, but the steam engine ended up remaking humanity…" by @stevenbjohnson #SocialMedia pic.twitter.com/agsGgBAlbJ

— Wesley Fryer, Ph.D. ??? wesfryer.com/after (@wfryer) March 14, 2017