Thanks to Greg Oppel and his presentation on December 6th at the Oklahoma Council for History Education symposium, “A. Philip Randolph: Service Not Servitude,” my wife and I watched the NetFlix movie “10,000 Black Men Named George” this evening.

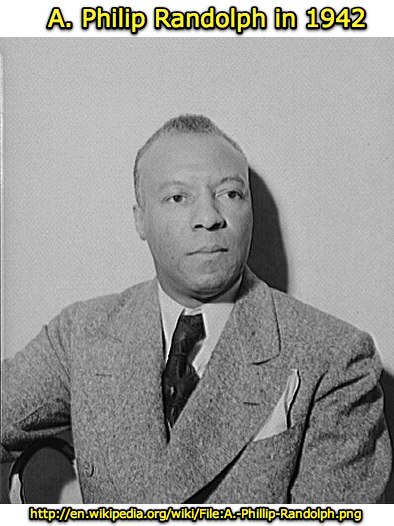

Philip Randolph was a courageous luminary from the U.S. civil rights movement who was not included (that I recall) in my own U.S. history curriculum as a student. That was one of the main points of Greg’s presentation, which is available via Ustream. All students of U.S. history and civil rights SHOULD know about Randolph just as they know about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Before I share a few reflections about Randolph and this film, I want to make a point about the power of asynchronously shared online video in this context.

There were only FOUR people in the audience for this outstanding and informative presentation by Greg at the Oklahoma Council for History Education symposium. Yet today, just two weeks or 14 days later, already the video has been viewed (at least in part) 244 times. This is AMAZING, and good. Welcome to the age of personalized digital learning. Want to hear Greg’s presentation? It’s online and available free.Webcam chat at Ustream

I hazard to say that in any other era of human history, a person off the street (like me) would not have been able to just show up for a local history conference presentation, obtain permission from the presenter to record and live-webcast the session, and then with technology tools brought in a backpack (a DV camcorder, a tripod, a Mac laptop and an AT&T 3G network USB laptop card) immediately share and digitally archive the presentation for a global audience.

This is an example of disruptive technologies put to a constructive use. 🙂

The movie “10,000 Black Men Named George” shares the early history of Randolph as the founder and chief organizer of the “Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters,” which in 1935 became:

… the first labor organization led by African-Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor.

According to today’s WikiPedia article for A. Philip Randolph:

Randolph emerged as one of the most visible spokesmen for African-American civil rights. In 1941, he, Bayard Rustin, and A. J. Muste proposed a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in war industries and to propose the desegregation of the American Armed forces. The march was cancelled after President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, or the Fair Employment Act. Some militants felt betrayed by the cancellation because Roosevelt’s pronouncement only pertained to banning discrimination within industries and not the armed forces, however the fair employment Act is generally perceived as a success for African American rights. An example of the success this act induced is in the Philadelphia Transit Strike of 1944 where the government backed African American workers against White labour. In 1947, Randolph,along with colleague Grant Reynolds, formed the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience. President Harry S. Truman abolished racial segregation in the armed forces through Executive Order 9981 on July 26, 1948.

These actions and contributions to the U.S. civil rights movement were VERY important. Yet as I have already stated, I don’t remember ever learning about Philip Randolph in school. I’m not emphasizing this point as a dig against my high school and college history teachers and professors, but rather to point out there are MANY voices and perspectives which may not have been emphasized in our textbooks or formal curriculum materials, but still deserve our attention and understanding.

The WikiPedia article for Randolph goes on to discuss the important role he played in the 1963 march for civil rights in Washington D.C., at which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Randolph was actually the first speaker at the podium that day, yet few U.S. citizens (including students) know or remember him.

Randolph was also responsible for the organisation of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963 with the help of Rustin and Martin Luther King, Jr. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is often attributed in part to the success of the March on Washington, where Black and White Americans stood united and witnessed King’s ‘I have a dream speech’. As the U.S. civil rights movement gained momentum in the early 1960s and came to the forefront of the nation’s consciousness, his rich baritone voice was often heard on television news programs addressing the nation on behalf of African-Americans engaged in the struggle for voting rights and an end to discrimination in public accommodations. He was also an active participant in many other organizations and causes, including the Workmen’s Circle and others.

I find this history lesson about American labor unions and the fight for worker’s rights extremely interesting as well as relevant amidst continuing battles in Washington D.C. and Detroit over a U.S. automaker bailout and the role of unions there.

Movies like “10,000 Black Men Named George” are very important to youngsters like me who do not remember the civil rights movement because we weren’t alive to experience and witness those days. This is RECENT history. And the struggles which leaders like Philip Randolph and many others fought in the name of civil rights and workers rights are not over. It seems to me that with the assassinations of both Dr. King and President Kennedy in 1963, for many people these historic struggles for equitable treatment and civil rights WERE (for practical purposes) over. Yet they were not and are not over.

As I hear about the high wages and seemingly ridiculous deals auto unions have negotiated for members to get paid even when they are not working, I’m also thinking about Philip Randolph and just how far we’ve come as a nation in the short 143 years since the end of the U.S. Civil War. It seems strange that today in many circles, the ideas of “workers rights” and organized unions sound outlandish and unpatriotic as they did in the 1930s when Randolph was organizing Pullman car porters. When I was a public school teacher in Texas, we were (as Texas teachers still are, I think) prohibited by LAW from striking. We could belong to teacher “associations,” but we were prohibited specifically from belonging to a “union.” Unions were considered evil in Texas, I was taught, and I didn’t really question the matter much at the time.

Of course the issue of whether teachers should organize and strike like blue collar workers is a contentious one, and I will not attempt to fully address that issue here. I do know that the fact teachers in many U.S. states are prohibited by law from striking seems outlandish to many educators in other countries with whom I’ve communicated in the past few years. “How do you have any power if you can’t strike?” some have asked. The answer: Teachers don’t have much power in many U.S. states, and that is by legislative design. Just as we see in the movie “10,000 Black Men Named George,” those in positions of power and control (which tend to be rich white men) tend to pass and support laws which support corporate interests over the interests of working people.

For local evidence of this, we need look no further than the teacher pay scale of public educators here in my state of Oklahoma. We rank 48th in the nation in teacher salaries. That’s right, 48th out of 50. And who is fighting to change this today? Where are the impassioned, bold voices today like Philip Randolph, organizing in the streets and the churches under the banner, “We need to pay our teachers more than a survival wage!?” I don’t hear or see anyone carrying this banner. This saddens me, and simultaneously emboldens me to learn more about both history and current events when it comes to civil and labor rights.

In my October 4, 2006, post “The causes of freedom and social justice” I wrote:

Where are our strong, visionary and courageous national leaders like Robert Smalls and Abraham Lincoln today? Where are our leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr.? What has happened to the dream of Martin and so many others who joined him in peacefully striving to end centuries of racial discrimination and segregation?

I am thankful for tonight’s opportunity to learn more about Philip Randolph and his historic struggles with many other leaders to improve the economic prospects of blacks in the United States as well as others. I won’t hide the fact, however, that I am also hopeful our new President-elect, Barack Obama, will lead our nation to again address issues of civil rights and worker’s rights which have not been addressed appropriately by a sitting U.S. president for many years.

We absolutely need to dispense with the ridiculous perception (advanced by U.S. political leaders who unfortunately have called themselves “conservative Republicans”) that most government regulation is evil and not needed. We absolutely DO need limits on the freedoms of both individuals and corporations to make economically expedient decisions at the expense of human beings, but these limits need to be reasonable. The website Behind the Label provides multiple examples of how the fight against sweatshops and unregulated business practices harmful to the basic human rights of people continues today. I AM an advocate for limited government, but “limited government” implies some regulations exist. Those regulations must address the same economic conditions and issues which Philip Randolph fought to change, and on which we still need to focus our collective attention and political will.

Union organizations have moved into the web 2.0 world to an extent, and the website Unite Here is one example. It strikes me (no pun intended) that we need a better balance between our ethical imperative to prevent the sorts of egregious exploitations of workers documented in films like “WAL-MART: The High Cost of Low Price,” and the over-the-top stranglehold which the Detroit auto unions appear to have over the U.S. auto industry in the name of “worker’s rights.”

Banning all teacher unions hasn’t worked to bring either Texas or Oklahoma educators to a place where they are paid suitably for the extremely important, pivotal role they play in our society. In Oklahoma, at least, I think this law continues to prevent teachers from speaking out and advocating for themselves, much in the same way Pullman Porters were intimidated and suppressed in the days before Philip Randolph fought to organize their first union.

I don’t have all the answers here, or maybe any of the answers, but I do have a lot of questions. If wisdom begins with the acknowledgement that “I don’t know,” perhaps I am on the right path. I do know I’m indebted to Greg Oppel for sharing the reference to this film with me two weeks ago at UCO.

My final observation is this. The corruption latent within Chicago and Illinois politics (as well as U.S. politics more generally) is highlighted several times in this film about Philip Randolph. Has anything changed?

Of course things have changed, but corruption is still with us. I hope the “publish at will” and storychasing tools now at many of our fingertips will serve as constructive forces of political transparency in the months and years ahead. The Change Congress movement embodies and operationalizes that hope and potential. The use of those tools for positive societal change, however, will continue to require courageous and visionary leadership, just as they did in the days of Philip Randolph.

The following organizations (endorsed by Change Congress) are also worth checking out and supporting on the issue of governmental transparency and reform:

You Street

Public Campaign

The Sunlight Foundation

SourceWatch’s Congresspedia

Maplight

OpenSecrets.org

Watchdog.net

Have a listen to this 4.5 minute recent interview with Larry Lessig for more background on Change Congress.

Technorati Tags:

philip, randolph, history, pullman, civil, rights, civilrights, struggle, mlk, martinlutherking