Where do I begin? Two articles published in The Economist‘s print and online magazines at the end of June 2013 are filled with errors and misleading statements concerning educational technology, testing, and school reform. The articles, “E-ducation: A long-overdue technological revolution is at last under way” and “Catching on at last: New technology is poised to disrupt America’s schools, and then the world’s” are both dated June 29, 2013. Here are the misleading statements, falsehoods, and outright lies the articles portray as truth in the name of further discrediting public school systems in the United States as failing, incapable of meaningful improvement or reform, and in need of private companies through charter schools and online programs saving the day after “evil teacher unions” are finally discarded by an indignant public sick of “lazy teachers” standing in the way of corporate America’s educational reform agenda.

Please remember, the statements below are the assertions and opinions of the authors of The Economist magazine (partly owned, not co-incidentally, by Pearson) NOT me. I am paraphrasing and summarizing the main points of the articles. I vehemently disagree with each of these assertions, in fact, and will provide links to support that opinion below under each subtopic. For additional reading and background on my perspectives on educational reform, please read my July 8th post, “Hallelujah: Oklahoma Withdraws from Common Core PARCC Testing Consortium.”

FALSEHOOD #1. NO PUBLIC SCHOOL IN THE UNITED STATES IS INNOVATIVE WITH EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY

The article “E-ducation: A long-overdue technological revolution is at last under way” begins with a paragraph which entirely ignores the fact that MANY U.S. public schools and school districts have embraced innovative ways to utilize digital technology in 1 to 1 laptop initiatives as well as other ways. This article does not identify a single public school district’s programs or initiatives as innovative. Only charter schools and private, corporate programs are highlighted. The article’s first paragraph ends with these words:

Ever since the 1970s Silicon Valley’s visionaries have been claiming that their industry would change the schoolroom as radically as the office—and they have sold a lot of technology to schools on the back of that. Children use computers to do research, type essays and cheat. But the core of the system has changed little since the Middle Ages: a “sage on a stage” teacher spouting “lessons” to rows of students. Tom Brown and Huckleberry Finn would recognise it in an instant—and shudder.

It is true our public school system in the United States continues to operate on the foundation of the Carnegie unit and “seat time.” It is completely misleading to conclude, as the article’s authors do, however, that computers are used in schools exclusively to “do research, type essays and cheat.” Certainly students use computers to do those things, but students as well as teachers do so much more! Computers are protean devices. Learners of all ages are using computers of various stripes, including mobile devices, to shift from being primarily passive CONSUMERS of information to more active and engaged CREATORS and PRODUCERS of information. That’s the focus of Mapping Media to the Common Core: What do you want to CREATE today? This project isn’t a pipe dream forecast of U.S. classrooms in two decades, it’s a current events lesson as well as prescription for MANY classrooms today.

The second article, “Catching on at last: New technology is poised to disrupt America’s schools, and then the world’s,” does briefly mention one public school district in the United States: Mooresville Graded School District in North Carolina. The article does not say the district provides MacBook laptops to all students in grades 4 – 12, as visitors can read on the district’s “About Our District” page. Instead The Economist authors wrote:

Over on the east coast Mark Edwards, superintendent of the Mooresville graded school district in North Carolina, introduced personalised learning on laptops for all pupils aged ten and over in 2009. His district is now one of the state’s leading performers, despite being close to the bottom in funding per pupil. Between 2009 and 2012 the share of its pupils considered proficient in maths, science and reading rose from 73% to 88%.

Readers of just the “E-ducation” Economist article might miss this and erroneously conclude we don’t have a single innovative PUBLIC school district in the United States.

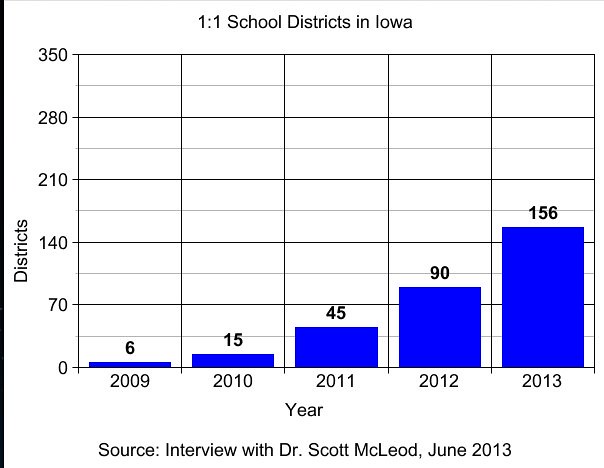

Did you realize almost HALF of all the 361 public school districts in the state of Iowa will be implementing 1:1 laptop learning programs in the 2013-2014 academic year in which students have access to their laptops BOTH at home and at school? (That’s what “1 to 1” means in Iowa.) According to Dr. Scott McLeod, who I visited with at the 2013 ISTE conference in San Antonio last month, these are the numbers of 1:1 schools in Iowa since 2009:

The specific locations of these schools are included in the Iowa 1:1 School Laptop Initiatives Google Map:

The fact that a school or school district has a 1:1 learning initiative is not a guarantee of innovative or transformative teaching and learning. It certainly is, however, a major example of an innovative approach to school learning with educational technology. While states like Iowa are literally overflowing with schools like these, the two June 2013 Economist articles leave readers with the impression that a single school district in North Carolina is the “lone innovator” in a sea of public school districts in the United States when it comes to educational technology use. That isn’t just misleading, it’s a blatant lie.

FALSEHOOD #2: PUBLIC SCHOOLS IN THE U.S. DON’T DIFFERENTIATE NOW TO MEET STUDENT NEEDS

Differentiating instruction and learning opportunities for students is a top priority for every single educator who cares deeply about students and strives to do their best every day in the classroom. Differentiation is very difficult, however, especially in an educational environment dominated by high stakes testing as well as a dizzying array of curricular mandates. Despite all these challenges, however, THOUSANDS of educators every day in the U.S. do an incredible job differentiating learning opportunities for students. These include students with mandated individual education plans (IEPs) as well as students on the “regular education plan” in schools. Could every teacher do an even better job differentiating learning for his/her students? Of course! Can technology play a powerful and constructive role in helping teachers differentiate learning for students? Absolutely! Is it accurate to portray all U.S. public schools as failing to differentiate to meet student needs today? Certainly not, but that is what we read in these articles from The Economist.

In both articles, Rocketship (a private charter school network) is highlighted for its effective use of educational technology to meet individual student needs. In the “Catching Up At Last” Economist article, authors wrote:

Teachers at Rocketship’s schools in San Jose earn 20% more than the local going rate, but will have up to 100 children in a class when they are working one-to-one in online learning laboratories. This gives Rocketship lower costs compared with schools of a similar size. It also means fewer teachers per pupil.

They go on to celebrate a recent rise in test scores at Rocketship:

Between 2009 and 2012 the share of its pupils considered proficient in maths, science and reading rose from 73% to 88%.

What, exactly, does “meeting individual student needs” at Rocketship schools mean, however? In her January 2013 post, “Rocketship to Nowhere,” Diane Ravitch concludes by writing:

The takeaway? These [Rocketship Schools] are schools for poor children. Not many advantaged parents would want their children in this bare-bones Model-T school. It appears that these children are being trained to work on an assembly line. There is no suggestion that they are challenged to think or question or wonder or create. But their test scores are high.

The Economist article authors present two different falsehoods regarding Rocketship schools in these articles:

- The Rocketship model is portrayed as one which could be readily generalized to all schools in the US to improve academic achievement, which it certainly could not. (Many parents wouldn’t want their children in a classroom with 99 other kids)

- It portrays Rocketship and other privately funded schools and charter schools as the only schools in the United States using educational technology effectively to differentiate instruction. That is patently false.

These Economist article authors paint U.S. education and schools with a broad brush, portraying schools as uniform and as remaining consistent throughout time. In “Catching On At Last” they wrote:

Over the course of the 20th century mass education produced populations more literate, numerate and productive than any the world had seen before. But it did so, usually, in an impersonal manner, with regimented rows of children chanting their times-tables as Teacher tapped the blackboard with a cane. Schooling could never be tailored to each child, unless you employed lots of teachers.

No one in any U.S. public school today (that I know of, do you?) is having children “chant times-tables as the teacher taps the blackboard with a cane.” In numerous ways in every public school, teachers are differentiating learning not only because they are required to by U.S. law for students with individual education plans, they’re also doing it (to varying degrees, of course) because it’s the right thing to do. The Economist article’s portrayal of zero differentiation in US classrooms is mistaken and misleading.

One of the best examples of using educational technology to meet individual student needs which I can point you to is the Google Search Stories video, “Cheryl & Morgan: Learning Independence.” It’s two minutes and thirteen seconds long. The PUBLIC schools featured in the video are in Wells, Maine. Yes, the teachers in Wells use educational technology in innovative as well as TRANSFORMATIVE ways to meet individual student needs. No, their schools are not privately funded charter schools, or pilot programs funded by Silicon Valley startup companies. Their schools are filled with passionate and dedicated educators like Cheryl Oakes, featured in the video, who finds ways to use educational technology every day to meet student needs. To differentiate.

Sadly, this perspective is missing from the June 2013 Economist article series.

FALSHOOD #3: EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY RAISES STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT (IGNORE PROVEN INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES)

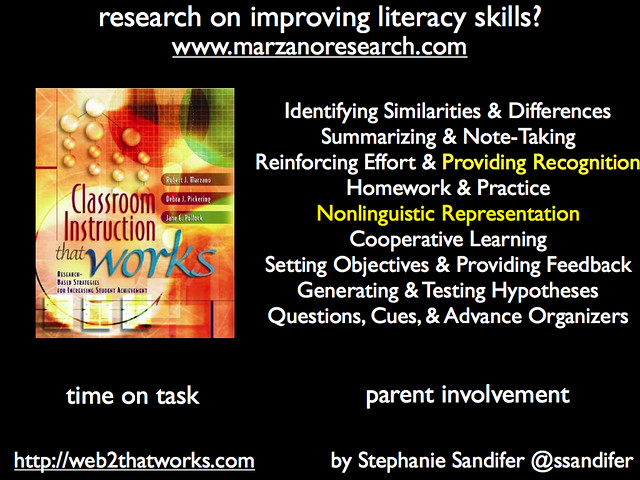

Educational technology does NOT raise student achievement. Proven instructional strategies, supported by educational research, do improve student achievement (including student test scores on assessment instruments which are both valid and reliable.) The following slide is one I frequently use in my presentations to highlight instructional strategies identified by Robert Marzano and his co-authors in “Classroom Instruction That Works” which meta-analyses of educational research conclude can improve student achievement.

In the June 2013 Economist articles, however, we read two different messages from the authors: Historic educational technology uses haven’t improved student learning and test scores, but new uses do.

In “Catching On At Last,” authors wrote:

A great deal of money went into computers for education in the dot.com boom of the late 1990s, to little avail, though big claims were advanced for the difference they would make. These claims were not entirely false: some bright, motivated children did use new technologies to learn things they would have missed otherwise. In many classrooms, too, computers have been used to improve efficiency and keep pupils engaged. But they did not transform learning in the way their boosters predicted.

These statements are correct, and supported by Larry Cuban’s 2003 book study of schools in Silicon Valley, “Oversold and Underused: Computers in the Classroom.” Simply having access to computers and technology does NOT increase student achievement or test scores. It’s what students and teachers DO with technology of any stripe (or any other instructional materials) that can make a positive difference.

The same article goes on to cite several specific studies of software programs like “Read 180” and “Cognitive Tutor,” and note that an Oakland school’s math scores have gone up in 2 years since students started using Khan Academy videos, but no actual research studies are cited. So much for “academic rigor” and “significant differences.” The way academic research studies are referenced and discussed in the article portrays our “new era” of private investment in educational technology and charter schools as offering “new reasons for optimism.” The article lauds “Amplify, the education arm of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation” along with other private companies developing adaptive curriculum and testing software programs as the solution our schools need to FINALLY realize the promise of the technological learning revolution in schools. In “Catching On At Last,” authors wrote:

Persuading schools to buy is only the first step, though. America’s teaching unions fear a hidden agenda of replacing properly trained humans with some combination of technology and less qualified manpower, or possibly just technology. Unions have filed lawsuits to close down online charter schools, including what looks like a deliberately obtuse proposal to limit enrolment at such virtual schools to those who live in their districts.

So, readers are to believe not only that new corporate funded software programs will be the test taking salvation of beleaguered students, parents and teachers, but also that teacher’s unions must be stopped at all costs since they oppose all constructive innovations like increasing student-teacher ratios?

Good grief.

FALSEHOOD #4: RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN STUDENTS AND TEACHERS DON’T MATTER

One of the biggest omissions in both these articles is any mention what-so-ever of the importance of RELATIONSHIPS in student learning and student achievement. In the classroom, relationships matter. For too long, our public policy discussions on education have ignored the importance of teacher-student relationships. This needs to end. We’ve likely all heard the statement, “Kids don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” This is true. Great years of classroom learning for my own children have been built primarily on good relationships with their teachers. Parents know how much relationships matter for student learning, but the writers of these Economist articles apparently don’t or are writing to support an educational reform agenda which isn’t interested in that fact.

No where in either of these articles do we read any kind of reference to the importance of teachers and their relationships with students. This is a huge omission.

FALSEHOOD #5: ONLY RICH KIDS IN RICH PUBLIC SCHOOLS GET TECHNOLOGY IN THE USA

Both these articles fail to mention Title I funding in the United States and portray “rich schools” as the primary ones which are and will benefit from educational technology. We do have rich/poor gaps in our schools and certainly have digital divides, but it’s misleading to portray wealthy or affluent schools as the only ones which are receiving educational technology. In the “E-ducation” article authors wrote:

Edtech will boost inequality in the short term, because it will be taken up most enthusiastically by richer schools, especially private ones, while underfunded state schools may struggle to find the money to buy technology that would help poorer students catch up. Governments will have to invest to allow them to do so. Some already are. In South Korea high-speed internet access is the norm in schools. Barack Obama recently promised that America will follow. Laws may have to be changed to allow pupils to study with those at a similar stage of learning rather than be grouped according to their age. But the biggest challenge for many politicians will be confronting the enormously powerful teachers’ unions.

It’s true we need to see more federal and state investment in educational technology access programs for public schools, particularly 1 to 1 learning initiatives. It’s false to say, however, that only rich or affluent schools receive edtech. Title I schools often have far more technology resources than more affluent public schools in the United States today, depending on how campus principals and other district officials have chosen historically to allocate those funds. It’s true many private and independent schools have embraced 1:1 learning more proactively than nearby public schools, but that’s not true universally. I’ve found this varies considerably depending on the VISION and LEADERSHIP of local leaders.

FALSEHOOD #6: U.S. CLASSROOMS DON’T HAVE ACCESS TO HIGH SPEED INTERNET ACCESS

Both these articles entirely fail to mention the E-Rate program in the United States, which since 1996 has provided funds to connect schools to high speed Internet networks as well as other communication networks. In “Catching On At Last,” Economist authors wrote:

At the beginning of June his [President Obama’s] administration announced a plan to give 99% of America’s students access to high-speed internet within five years.

There are definitely many problems with our E-Rate program and the ways schools have used and been allowed to use those funds to support learning, but these articles make no mention of the BILLIONS of dollars U.S. taxpayers have spent over the past 17 years to connect our schools and libraries to the Internet.

The previous “E-ducation” article quotation including the statement “Barack Obama recently promised that America will follow” makes it sound like “high speed Internet isn’t the norm in U.S. schools today.” It IS the norm. I don’t know of a single U.S. public school still using dial-up Internet services. Not all students have wifi access for BYOD devices (including my own kids in Oklahoma City Public Schools) but wifi is the norm for teachers and for students accessing online resources in places like the library and computer labs. These articles from the Economist are misleading when it comes to the complete lack of high speed connectivity they portray our students and teachers having in public schools.

FALSEHOOD #7 NCLB AND RTTT CAN BE CREDITED WITH ENCOURAGING INNOVATIVE USES OF EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY IN CLASSROOMS

Undiscerning readers of the Economist article “Catching On at Last,” might mistakenly be led to believe that the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and Race to the Top (RTTT) programs have encouraged innovative uses of educational technology in U.S. classrooms. The exact opposite is true, however, both these programs have widely encouraged teachers to “teach to the test” and have not supported any innovative, blended learning programs like 1:1 laptop initiatives. The article authors state:

The main reason for optimism, though, is the evidence coming in from classrooms. Adoption of education technology in America’s state-funded schools was given a boost by a requirement to measure pupil performance in the No Child Left Behind Act, signed by George W. Bush. Online learning was first picked up in some surprising places, including rural Idaho, where schools were looking for ways to expand the limited curriculums they were able to offer. Barack Obama’s Race to the Top initiative gave a further shove, making billions of dollars available to states willing to innovate. At the beginning of June his administration announced a plan to give 99% of America’s students access to high-speed internet within five years.

NCLB did not have ANY provisions encouraging innovative uses of educational technology by students or teachers to raise student achievement, as far as I know, other than mandates to focus on DATA gathered from high stakes, punitive tests for students. That is certainly NOT a “reason for optimism,” quite the opposite: It’s a reason many teachers have become depressed, unmotivated, and chosen to leave the profession in disgust. The Twitter profile of Seattle educator Mark Ahlness reflects this.

It is incredibly disingenuous and misleading (to choose tactful words) for Economist authors to portray NCLB and RTTT as supporting innovative uses of educational technology in U.S. classrooms, when they have done EXACTLY THE OPPOSITE. The only support article authors provide for this is mentioning an expansion of online learning options. There are multiple reasons which account for the explosion of online learning options for students, and legislation has played an important role. See my March 2009 post, “Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns (CoSN 2009 closing keynote)” for more on this. For now I’ll just note it’s HUGELY disingenuous to conflate an increase in online learning options for students in U.S. public K-12 schools with educational technology innovation and particularly to give credit for such “innovation” to NCLB and RTTT.

FINAL CONCLUSIONS

I shook my head and sighed deeply when I read both these articles tonight, thanks to a tweet on July 8th from Rhode Island’s Commissioner of Education, Deborah A. Gist. We are in a tectonic struggle in our nation when it comes to changing the destructive momentum of our educational policies over the past several decades. Articles like these from the Economist are part and parcel of an ongoing campaign by many “corporate education reformers” in the United States whose true objective is NOT improving learning opportunities for students, but rather destroying our public schools and our system of public education which continues to be a critical part of our representative democracy. Later this summer I’ll be reading “Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland?” by Pasi Sahlberg, and I’m hoping to hear Sahlberg in person next February in Saskatoon during their Festival of Education. We CAN, in the United States as they did in Finland, articulate and support a constructive reform agenda for education which will transcend political parties, further professionalize rather than demonize teachers, and provide outstanding learning opportunities for students in classrooms in all our schools. That struggle is not going to be an easy one, but it’s the task which is before us.

Unmasking misleading and false statements, like many of the assertions made in this Economist article series, can hopefully play a constructive role in this struggle. Teachers are not the enemy, nor are all teacher unions. Charter schools and private startup companies are not the salvation messiahs for the challenges which we face in our public and private schools. As I tweeted today during the special OKCPS Board retreat, “Good people in teaching & administrative roles IS the key.” Relationships matter. Powerful tools like educational technology resources can be utilized for hugely beneficial purposes, but alone they will not improve student achievement or student test scores.

[END OF RANT]

If you enjoyed this post and found it useful, subscribe to Wes’ free newsletter. Check out Wes’ video tutorial library, “Playing with Media.” Information about more ways to learn with Dr. Wesley Fryer are available on wesfryer.com/after.

On this day..

- Understanding Russian Disinformation in U.S. Politics – 2019

- Road Trip Wireless Devices (July 2014) #SignOfTheTimes – 2014

- Create Make and Learn Conference: Day 1 Making Media Recap – 2014

- Leveraging YouTube to Tell The Story of Your Non-Profit – 2012

- Add Video Annotations to a YouTube Video – 2012

- FAQs About iPads and Media in the Classroom – 2012

- How to Talk to Your Students About Copyright – 2011

- Avoid Double Cross-Posts from Twitter to Facebook using Visibli and Selective Tweets – 2011

- Think Before You Tweet – 2010

- Finding Balance – 2009

Comments

4 responses to “Getting it WRONG: The Economist on Educational Technology, Testing and School Reform”

I wanted to point out that many charter schools do recommend the employment of a 21st century chanting and cane tapping formula. In the book “Teach Like A Champion” they suggest choral response to teacher call outs.

Hi Wes. Great rant, and I’m glad to hear you’re still seeing innovation with technology happening in some places. From where I sat, it had been a lost cause for a long time. Out here, computing devices are seen as ways to give high stakes tests – and real convenient appliances to sit kids in front of for hours (and yes, they are counting them) in packaged “curricula” – to raise high stakes test scores. A couple of things really sadden me about this – kids grow up thinking that’s what computers are for, and teachers, especially newer ones, think this is teaching. Ugh.

I am happy to hear that you and others are still pushing, swimming hard against the stream. I have to believe your work will make a difference!

These days, I get as involved in pushing back against the whole reform agenda as my blood pressure will allow, protect myself whenever necessary with a Data Shield http://ahlness.wordpress.com/data-shield/ – and am grateful that I still have a chance to teach meaningful things, and even blog a little about it: http://pikeplacemarket.edublogs.org/ – imagine that 🙂 All the best! – Mark

Boy, Wes, you were really pissed! Great rebuttal, I hope they read it.

[…] Una crítica sobre la actual reforma educativa en EU y su relación con los mitos innovadores de la … […]