I’ve read a couple articles recently about memory, the brain, and the fundamental ways our access to information and knowledge has changed which have me thinking.

Clive Thompson referred to the idea that “the information/knowledge is in the network” in his September article in Wired magazine titled, “Your Outboard Brain Knows All.” Thompson cited Cory Doctorow’s March 2002 article for the O’Reilly Web DevCenter “My Blog, My Outboard Brain” as being the original source for this term, “outboard brain.” I hadn’t read that article by Cory previously or heard this term, but it makes sense. George Siemen’s 2004 article “Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age” explores this idea that our information and knowledge landscape has changed in fundamental ways because so much “stuff” is now accessible at our fingertips IF we are connected via the Internet to the World Wide Web.

I thought about these ideas tonight at dinner, as I heard my wife ask my 4th grade son how he was coming in memorizing the fifty U.S. states and their capitals. Why are kids in school still memorizing the fifty states and capitals? I think there is an obvious reason: They’re still doing this because the activities of many schools are more driven by TRADITION than they are driven by learning needs, learning theories, workforce needs, or educational research. This reminds me of Tevye’s song “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof. Traditions are powerful things, and in many cases I think they continue to drive our schools much more than common sense or the actual learning needs of our students.

The irony of “traditions” revolving around memorizing facts, many of which are frankly useless, and prohibiting students from using the tools at their fingertips via cell phones as well as laptops was driven home to me last spring when I shared a presentation for the Rotary Club in Duncan, Oklahoma. During the meeting, two high school students were recognized for their academic achievements and were presented with Rotary scholarships, as I recall. Before receiving their scholarships, however, each student had to answer some factual trivia questions posed by one of the Rotary members. One of them either had a cell phone or PDA, or someone else did at the meeting, and the person asking the questions made a big point to say (to the effect) “Put away your cell phone or electronic devices. You can’t use any of those tools to answer these questions.”

Why should we force students to put away their electronic devices when they need to answer questions? Rather than ask basic, simple questions like “When did the United States declare war on Japan and enter World War II?” why don’t we ask a question that requires higher order thinking, like “Explain the significance of the Doolittle Raid on U.S. morale during 1942?” It was actually very sad to see these Rotarians grilling VERY smart high school students with unrelated trivia questions which neither were able to answer successfully. The message of the event seemed to be, “See how these kids really aren’t that smart after all?” This was unfortunate, because these kids were and are very bright. Ask any person on the street a very detailed, fact-based question about history or geography and you’ll likely turn up with wrong answers. Jay Leno and other late night television comedians seem to demonstrate this frequently with their “person on the street” interviews. Does this show that people are dumb? I don’t think so. I think it often shows that we persist in asking people dumb questions, and fail to realize their answers to those knowledge and comprehension level questions don’t reflect their actual intelligence or understanding of often complex ideas and historical events. Don’t get me wrong, I do think many people are less informed than they should be about many current events and situations involving both domestic and international politics. That said, however, I still don’t think failing to succeed in a “Quiz Bowl” style trivia contest or a spelling bee correlates to a person being dumb or not intelligent.

The fact that my own children are regularly taking spelling tests at school continues to both trouble and irritate me as well. There is virtually NO academic research I read or was exposed to in my masters and doctoral graduate coursework in education which suggests giving students spelling tests of decontextualized words on a weekly basis improves their abilities to spell, read or write. The real skill related to spelling is WRITING, and the best way to improve writing skills (according to the body of literacy research reviewed by Dr. Stephen Krashen of USC in his excellent book, ““The Power of Reading, Second Edition: Insights from the Research” is to encourage students to READ prolifically. My son, like his mother, is simply not a speller. His brain is apparently not wired to visually remember the spelling of words, and he’s regularly done poorly on spelling tests. I am absolutely, positively not worried about this. Since this summer when he started reading the Harry Potter books, he has been voraciously consuming literature. Alexander’s love of reading can be traced back to the book “Eragon” by Christopher Paolini, which was his first “home run book” (a term by Jim Trelease) that I wrote about back in January in the post, “The Power of Reading.” This past Saturday, Alexander finished reading the 5th Harry Potter Book, and just this week already (it’s now Wednesday) has read almost three-fourths of the 6th Harry Potter book. He is reading voraciously. He’s writing on a weekly basis, not only in school (where I honestly hope he’s writing, but I’m not sure) as well as on our family learning blog which we started a couple of weeks ago. Whether or not he does well in 4th grade spelling, whether or not he is eliminated in round 1 of the school spelling bee (which interestingly he has expressed an interest to compete in) and whatever his 4th grade language arts grade might be at the end of the year– I have complete confidence that my son is already part of “the literacy club” and he’s going to be a lifelong reader. Hopefully he’ll cultivate a love of writing and written communication as well, but that remains to be seen. The modeling he’s seen at home for reading as well as writing will probably be important influences on him in this regard, but ultimately it’s up to him to make choices about how he best enjoys expressing himself and sharing his ideas. Give a listen to my interview with him last Sunday after he finished the 5th Harry Potter book to get a better idea of the level of thinking he’s been doing about the themes and characters of J.K. Rowling. Clearly this boy loves reading, and once you’ve discovered and cultivated a love of reading I don’t think there is any “going back.” 🙂

The other article related to memory and information that has me thinking recently is Joshua Foer’s November 2007 article “Remember This” in National Geographic magazine. On page 36, Foer tackles the fascinating question, “What is a memory?” Despite all our technology, despite all the science and “claims” we make about knowledge and the nature of reality, we still have very little idea how neurochemicals become thoughts. Foer writes:

What is a memory? The best that neuroscientists can do for the moment is this: A memory is a stored pattern of connections between neurons in the brain. There are about a hundred billion of those neurons, each of which can make perhaps 5,000 to 10,000 synaptic connections with other neurons, which makes a total of about five hundred trillion to a thousand trillion synapses in the average adult brain. By comparison there are only about 32 trillion bytes of information in the entire Library of Congress’s print collection. Every sensation we remember, every thought we think, alters the connections within that vast network. Synapses are strengthened or weakened or formed anew. Our physical substance changes. Indeed, it is always changing, every moment, even as we sleep.

Back in 1999 (or so) I had an opportunity to attend and present at a Houston-area education conference where the keynote speakers were a husband and wife team who focused their studies (and presentations) on “brain research.” Brain research is one of those ever-popular professional development topics at workshops, and for good reason. As educators, we SHOULD be vitally interested in ongoing research about learning and the brain. Two of my biggest “takeaways” from that keynote address were that the brain CAN create new neurons (neural pathways or connections) even as we age, and that one of the keys to the formation of new neural pathways is curiosity and novel experiences. The presenters showed a compelling video (authentically compelling since I still remember it over 5 years later) which showed retirees participating energetically in a wide variety of creative arts at their retirement community. These mature adults were painting, making music, and even creating sculptures. The novel experiences of the creative arts literally helped these older adults stay young, as well as have fun learning new things. Writing on page 38 of the article, Foer noted:

Intellectual and social engagement, many researchers believe, helps slow mental decline. “We have to rethink every single component of how we’re caring for our elders,” says [Nancy] Wolske, because “the people they were are still there.”

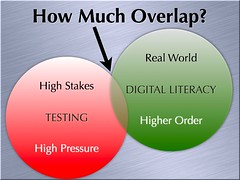

In addition to rethinking the way we care for the oldest and most mature members of our society, how about rethinking the ways we care and attempt to nuture the learning of the youngest members of our society? We MUST reinvent our schools in the 21st century. This is not an option, it is a moral imperative. To fail in this mission would not only let down our own children, it would invite a bleak future possibly bankrupt of creativity and passion for learning. Have you been in a classroom lately where the “pressure is on” to get ready for the test? Have you sensed a great deal of “intellectual and social engagement” in that environment driven by the threat of punitive test consequences? There is a wide gap between the skills employers tell us they want for new hires in the workforce, and the skills emphasized in a high-stakes testing environment in schools. I summarized this almost two years ago for a presentation I shared at the TCEA conference. My first question was, how much overlap is there in the skills encouraged and needed in these two different environments?

The sad reality, in many cases, is that the skills emphasized and needed in these two contexts appear to be mutually exclusive:

That presentation from 2006, btw, is available as an audio podcast.

To connect these ideas back to Cory’s idea of the “outboard brain,” let’s think about how COMPLETELY different our information and knowledge landscape is in 2007 compared to every other era of human history. In the past, students in schools memorized facts and even works of literature because they didn’t have an alternative if they wanted those ideas to be readily at hand, “at need.” In his National Geographic article on memory on page 49, Foer wrote:

“Ancient and medieval people reserved their awe for memory. Their greatest geniuses they describe as people of superior memories.” Thirteenth-century theologian Thomas Aquinas, for example, was celebrated for composing his Summa Theologica entirely in his head and dictating it from memory with no more than a few notes. The Roman philosopher Seneca the Elder could repeat 2,000 names in the order they’d been given to him. A Roman named Simplicius could recite Virgil by heart—backward. A strong memory was seen as the greatest of virtues since it represented the internalization of a universe of external knowledge. Indeed, a common theme in the lives of the saints was that they had extraordinary memories.

Is a genius today someone who can recite a complete work by Virgil? Say aloud all the U.S. states and capitals from memory? Someone who can successfully compete on the Fox television program, “Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader?” Someone who can ace a spelling test?

I don’t think so.

I won’t pretend to know what really defines a “genius.” I do perceive that people who can synthesize ideas from different areas or disciplines, see new connections, and make new discoveries DO have a remarkable DEPTH of knowledge which is tied to specific facts and ideas. Those people aren’t simply generalists, they ARE experts on various subjects. The need to be able to have so much information MEMORIZED and stored directly in your brain for ready access appears to be FAR LESS important than it was in the 1st century A.D., however.

Shouldn’t the predominant learning activities and assessment tasks of students in our schools reflect this changed reality? That sounds quite reasonable to me. Unfortunately in many schools, tradition continues to trump common sense, or as Larry Cuban argued in 1986 in “Teachers and Machines,” innovation is silenced and eliminated by “the logic of the classroom.” It may be time to STOP calling our places of learning in schools “classrooms” and instead, following the suggestion of Clarence Fisher, call them “studios.” Personally, I think the cognitive baggage I associate with the term “studio” reflects much more accurately the sort of learning environment I want for my own children in schools than the word “classroom.”

Words matter. Perhaps it’s time we change some of the basic vocabulary terms we use in schools. Students and teachers are both LEARNERS. They alternate, depending on the context, between the roles of expert and novice learner. The places where they learn together are called “studios,” not “classrooms.” And as Sharon Betts encourages, the work they do is regularly published on the global stage for an audience of international reviewers. Sound like a pipe dream? Maybe. But it’s up to us to be the catalysts which usher in this new age of authentic learning in schools. Always keep in mind the wise words of Margaret Meade:

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

I’m feeling quite thoughtful and committed at this point in my life when it comes to the topic of educational megachange. What about you?

Comments

12 responses to “The outboard brain, memory, transfer and learning”

Wes,

I am a sped techer who has to give a high stakes test to high school students who are at their

best working at 6th grade level and tell them that if they don’t pass they will not graduate.

Many of these students just don’t have a good memory system for facts, but they are good

problem solvers. We should be giving them the tools that are at hand and teach them to use the tools

to solve problems and communicate with people who can help them.

But, they also need a walking around knowledge of the their envornment, like New Mexico is a state, the function of Congress, times table. To pull out your cell phone to divide 20 by 5 is not the correct use of the tool. We have to be careful that we don’t “outboard” esential knowledge.

I like the term learning center for school and I agree that teachers have to not be the guardians of knowledge, but role models as learners.

Wow, Wes! As usual you’ve tossed a lot meat on the BBQ here! Just to expand on one of these points, “The message of the event seemed to be, “See how these kids really aren’t that smart after all?””

This is so true – we aren’t very comfortable with smart kids. I see it all the time. No matter what a kid does right, there’s always someone to point out what they are doing wrong. Do you think this is just in the US? Is this just about anti-intellectualism or do you think it’s specifically about adults needing to feel superior? Or another reason?

Whatever it is, I think it fuels the mindset that allows us to treat students as objects that need content “delivered” to them and can be mass-tested. Until we can acknowledge individual gifts and capabilities in kids, we won’t see them at all. I’m not sure brain research or renaming classrooms helps that.

Thanks for kick starting my morning!

It’s true that higher thinking skills need to be part of the classroom more than they already are, and that nearly any information we wish to acquire can be found on the internet. But in order to develop those higher thinking skills, it is necessary to have a base of knowledge memorized. I think it’s important to be consciously aware of the geography of the world you live in, etc.

Without a working scheme new information/knowledge/skills don’t make any sense and will not be attached to the neural network.

Instead of taking away electronic tools groups such as the Rotary should embrace them. They should ask the kids to demonstrate them and explain how they can be used in the everyday world.

Whew, that’s a lot to process. I’ll have to comment some here and blog the rest. Is there no place for memorization in education? Isn’t great writing heightened by reference to famous phrases from literature (“Abandon all hope ye who enter here…”) and poetry (“Water, water everywhere and…”?) If you do not have those famous phrases from great American documents (“We hold these truths to be…”) and classic literature (“et tu Brute?”) already in memory how can you add them to your writing? I am an old English major, so I am partial.

I do remember your point that these factoids are pulled kicking and screaming out of their context and not used to add a rich and subtle background in writing. You point is rather the opposite of my paragraph above, that spelling tests are given outside the context of reading and writing. That the states and capitals are tested outside the context of their history.

R08 said “in order to develop those higher thinking skills, it is necessary to have a base of knowledge memorized.” It is Ok to memorize as long as it is the beginning of knowledge, not the end. Knowledge needs to be deep instead of shallow memorization.

I should have just blogged the whole blooming comment because it got too long for one comment. This comment is a defense of spelling tests.

I do give spelling tests (mainly because I have to give a spelling grade. I have noticed a curious corollary between reading scores, writing ability, and spelling scores. Those who struggle with reading and sometimes writing often have trouble spelling. I think it is because most of our English words are spelled phonetically or follow sound-to-letter rules. Phonics and phonetic awareness are two of the five facets of teaching reading, so those weak in phonics are weak in reading and spelling. The short of that long premise is that I think spelling test are fairly valid tests of student reading(and maybe writing) ability. Maybe they are just not testing what we think they are testing.

That being said, I still don’t like giving spelling tests outside of the context of writing.

Wes, I have been contemplating this too as I have been teaching a basic chemistry unit. Generally speaking, I ask my students to memorize nothing that they can look up. This last week I found myself requesting that my students memorize the symbols of 40 of the most common elements encountered in chemistry. Why did I do this? Because we are starting to create screencasts where students produce teaching videos regarding ionic and covalent bonding as well as balancing of chemical equations for their peers and others I need them to be able to at least recognize basic symbols such as H for Hydrogen or Cl for Chlorine so that they can proceed forth with higher order thinking skills and not be bogged down with looking up every symbol.

Many of us have memorized an encyclopedia of information over the years of our schooling yet what remains is the ability to synthesize and analyze divergent pieces of information- and to be creative with this analysis. Many of us would not have reached anything close to to our current intellectual capacity without some basic foundational roots.

We teach what we know and how we have learned. In my mind here lies the problem. The world of information and literacy races forward at a logarithmic pace meanwhile so many of our educational systems and pedagogy are stuck at a linear, nearly flat line pace. This is a pace that is rooted in a past of Encyclopedia Britannica knowledge (and perhaps the memorization of 40 common element symbols) as opposed to the world of Wikis and rapid evolution of concepts, information, and knowledge. Thankfully, we have a few practitioners in the classroom that can take foundational knowledge and move it into logarithmic phase using new tools that stretch analytical thought and creativity. Being able to recall that “H” stands for hydrogen isn’t going to give anyone an edge in our current global economy- but being able to do something with this knowledge might! ( Still waiting for my hydrogen powered car.) Cheers and love your thoughts…

Good feedback here. To your points James, yes– CONTEXT is the key. My beef is most directly with decontextualized spelling tests, which seem to be everywhere. I’d challenge you and others to find sound educational research which supports spelling tests. It’s not out there, from what I’ve learned. I can dig into my notes from my doctoral literacy classes and pull some of the research that indicates spelling tests are not effectual. I think schools tell teachers to give spelling tests because they are easy to give, easy to grade, and we’ve always done them. It takes virtually no instructional or pedagogic skill to give a spelling test. The custodian or a substitute teacher with zero instructional knowledge can give a spelling test (and even grade it) just as effectively as a master teacher. I know there are realities like “I have to give a grade on spelling” – my encouragement here is for teachers as well as administrators to examine their own practices, and ask if there are good reasons to persist in the instructional tasks and assessments which we generally accept because of our own past experiences with them and their ease of implementation, rather than whether they are good for kids or learning.

In terms of the reading/writing connection and spelling, again I’d refer you and others to the research rather than just your own experiences and perceptions. Certainly our own experiences are an important lens for considering our instructional practices, and I won’t discount that. But again, look at what Krashen says in his meta-analysis (“The Power of Reading”) of educational research on literacy development, first and second language acquisition, reading and writing. The spelling link you’re putting faith in isn’t there, from what I’ve studied.

My son is a case in point. He just finished reading the 6th Harry Potter book last night about 9 pm. That was Thursday night. He started the book on Sunday. He is 9 years old, almost 10, and in the 4th grade. He read the 600+ pages in five days and can discuss the plot, characters, controversies, etc in detail. His comprehension of the text he read is very high. Yet he has extreme, consistent difficulty passing a decontextualized spelling test. So at a personal level, I see him as a specific example and counter-point to your perception that “giving kids spelling tests will help them be better readers.”

If we want students to be better readers, we have to provide them with access to diverse types of texts, give them choices about what they read, provide TIME for them to read, and support them in their reading in various ways. That does not mean pushing an extrinsic reward system like AR for students. Reading for enjoyment has it’s own rewards. We want students to read not because they have to, but because it is wonderful and they love it. As Alexander and I were discussing last night, reading a book like Harry Potter can literally transport you into a different world. When students have discovered this, their reading AND writing AND spelling skills will improve. This is not rocket science. And it is well documented/supported in educational research, not just my own personal experiences.

Joselyn: You are right that we have to have specific knowledge about things to understand and think about ideas deeply. My beef is that too often we stay at the superficial level. Some memorization is certainly needed. I had to memorize a ton of things in my educational background and I know that helped me develop the schema which gives present meaning to me in many contexts. I guess I don’t see this as an either/or proposition. Many arguments in education are portrayed that way and I think that can be harmful. Phonics or whole language? My answer is both. Kids are different, and they learn to read in different ways. If phonics helps them, great. The main key is READING. Phonics does not work for everyone. Is knowledge transmitted or constructed? It’s mainly constructed, but information can also be transmitted (or “delivered”) in compelling ways. Do do we need classrooms focused entirely all on process with no content? Certainly not! When it comes to memorization and synthesis, again I think we need a balance. This makes me think of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The knowledge and comprehension level is at the bottom of the pyramid. You need to know the elements and about them to think at higher levels about them. So there IS a place for memorization. In many cases, however, I think the focus on memorization is misplaced. The U.S. states and capitals are an example. You have GOOD reasons for having students memorize things about the periodic table. I don’t think most teachers have compelling reasons to have students memorize states and capitals, other than the fact that they’ve always given that assignment and it’s very easy to do and assess.

Great comments, great thinking. Keep it coming. You all are challenging me and I love it. 🙂