As a society we are witnessing a tectonic shift in the way video content is created, distributed, and consumed worldwide. Research like the 2010 Horizon Report makes the ascendency of the mobile web and proliferation mobile devices which access the Internet clear to see. Increasingly, content consumed on mobile devices includes videos as well as text and still images. This was brought home to me recently over the Christmas holidays, when I watched my favorite NCAA football team play their bowl game on my iPhone when I was “out and about” away from the house. Doing this was a dream a few years ago. Now it’s a reality, not only thanks to mobile devices but also high speed cellular network towers in our community. Ubiquitous, high speed wireless connectivity isn’t a reality in many rural areas, but it is for many urban residents in more parts of the United States than ever before.

In the middle of the mobile web and mobile video revolutions are an array of corporations angling to remain profitable leveraging consumer demand for mobile media. The “browser wars” of the 1990s which pitted Microsoft IE versus Netscape have become more diversified and interesting today, with Mozilla FireFox, Apple’s Safari, Google’s Chrome, and Opera joining Microsoft’s Internet Explorer in the battle for web surfer eyeballs. (FireFox is, btw, the grandchild of Netscape.) The video codecs which run within these browsers, both on computer desktops/laptops and on mobile devices, as well as the codecs used to produce video are also diverse. Last week, an announcement was made which demonstrated (if we didn’t already realize it) that the video codec world is just as contentious as that of web browsers.

Google posted an initial announcement on January 11th, and followed up with a lengthier post on January 14th, explaining that the Google Chrome web browser would be dropping its support of H.264 video. Instead, Google’s Chrome browser will offer native support for the “open” WebM video codec it continues to co-develop with others. Google has confirmed it will still continue to encode and serve (for the present) videos on YouTube in H.264 format, but there is no guarantee that routine will continue indefinitely. While some observers saw this announcement as an attack by Google on Apple for control of video codecs, others concluded it has everything to do with Google’s costs to maintain infrastructure /server farms for YouTube videos which continue to explode in number and file size. Since mobile devices as well as web browsers without built-in support for H.264 video playback rely on Adobe’s Flash software technology, some other analysts saw this move by Google as supportive of Adobe and its Flash format. This is a confusing landscape of acronyms, companies and agendas, and no consensus seems to exist at present about what all of this means for the future of web video. What is clear is that these actions and decisions involving WebM, H.264, Flash, and Silverlight are very important for the future of web video and Internet-based communication. In this post, I’ll try and clarify (both for readers as well as myself) who the players are and what their respective formats as well as agendas appear to be at this point.

Before I go further, let me offer reassurance to iOS (iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch) owners wondering if YouTube is going to suddenly cease to be a video option on those devices. It isn’t. According to Charles Arthur’s article for the Guardian yesterday, “Google provides new answers on H.264, WebM/VP8 and YouTube: mud clears somewhat:”

YouTube isn’t giving up H.264. At all. You can, if you’re determined, get WebM/VP8 content on YouTube (both to contribute and download). There’s the possibility that it [Google] is re-encoding all its content into WebM – just as it did to H.264 in June 2007, when the iPhone was about to arrive. That took something like three or four months to do. The library is bigger now, but so is Google’s processing power… this isn’t going to affect the mobile side – so iPhones, iPads, iPod Touches are not going to go dark [without YouTube content.]

Two excellent resources which provide background about these issues are the YouTube HTML 5 Player information page, and the current WikiPedia article for YouTube: Specifically the section on “Quality and Codecs.” The article explains:

In December of 2010, YouTube got rid of the option to automatically play videos in a specific format, depending on the URL, via putting “&fmt=xx” (“xx” determines one of ten different two-digit numbers) in the URL.

When you click the “embed” button on a YouTube video now, you’ll see the option to “Use Old Embed Code” if you don’t want to use the new format.

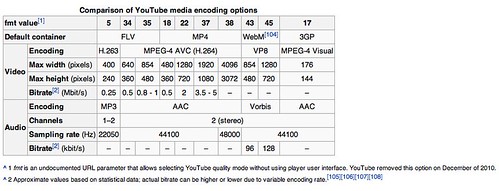

In the graphic above from the WikiPedia YouTube article, you can see four “default containers” for videos served by YouTube at present are FLV (flash,) MP4 (not synonymous with H.264, which is the codec used for encoding,) WebM (the open format supported by Google and others) and 3GP (a cell phone format.) H.264 video is supported most prominently by Apple and Microsoft. Google pays millions in licensing fees for the use of H.264 on YouTube to these companies, as Wolfgang Gruener explained in his article yesterday, “Google and H.264: You Would Have Dropped It As Well.”

Let’s look at the possible negative impact of dropping (native) H.264 in Chrome and what “evil” strategy could be behind this decision. Your best argument would be a shot against Apple and Microsoft, as both are the strong supporters of H.264 and two of the 26 patent holders of H.264 technology. Why support a tech that requires up to $6.5 million in annual license fees and fund your enemies, if you do not have to?

In terms of the browser battles, Apple’s Safari web browser and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer 9 include native support for H.264. So does Apple’s version of webkit for its iOS devices. (IE 9 is just available for Win7 and Vista, however, not WinXP. I agree with Charles Arthur this was a dumb move by Microsoft.) Webkit is the engine which also powers the Google Chrome browser, but native H.264 support is what Google announced last week it’s dropping from Chrome. This does NOT mean Google Chrome won’t be able to play H.264 video, however, it just means it will rely on the Flash plugin (like the Opera and Mozilla FireFox browsers do) to play them. This is why some analysts viewed Google’s announcement about WebM to be a victory for Adobe. Long term, I don’t personally thank that is an accurate assessment.

Before I leave the topic of players, I need to mention Silverlight. Silverlight is a Microsoft-developed video streaming technology, and is used today by Netflix to stream TONS (to use a non-technical unit of measurement) of web video to consumers’ televisions, computers, and mobile devices. Other folks use Silverlight, but Netflix is the most well-known user. Silverlight isn’t a codec of interest to UCG (user generated content) advocates, but it is important for commercial “pay for the stream” services like Netflix.

To consider Google’s side of this announcement and controversy, we should acknowledge their argument that the issues at stake go beyond licensing fees and bottom lines. Their January 14th clarification post contends innovation on the web is also at stake if H.264 is allowed to become the dominant standard for web video:

But it’s not just the license fees; an even more important consideration is the pace of innovation and what incentives drive development. No community development process is perfect, but it’s generally the case that the community-driven development of the core web platform components is done with user experience, security and performance in mind. When technology decisions are clouded by conflicting incentives to collect patent royalties, the priorities and outcome are less clear and the process tends to take a lot longer. This is not good for the long term health of web video. We believe the web will suffer if there isn’t a truly open, rapidly evolving, community developed alternative and have made significant investments to ensure there is one.

Some analysts, like Dan Frommer, argue Google’s talk about “openness” is all hypocritical and a “crock.” I’m far less cynical. Certainly Google has many closed-source software projects like other companies including Apple and Facebook, but WebM as well as the Android mobile platform are bonafide open source initiatives which include numerous developers and third party partners. We can debate whether the current quality of the open-source based Android platform is inferior to Apple’s iOS, but it seems silly to deny its inherent openness. Google supports closed software development as well, but it’s making big bets on the potential and power of “open” when it comes to mobile devices as well as web video.

What about Apple, you may ask? “I thought Apple was a champion of open technologies with HTML5,” you might say. Well, HTML5 certainly IS an open standard, but H.264 is not. As a partner with Microsoft in the group which controls H.264, Apple has a strong financial stake in the future of it as a video standard. When you hear Apple representatives talking about “our support of open,” remember (as is the case with Google) it’s THEIR VERSION of supporting “open.” From Google’s perspective, support of HTML5 with H.264 video encoding is NOT “open,” since it involves the payment of millions of dollars in royalty payments. WebM video, on the other hand, IS truly “open” since its development is an open process and use royalties don’t apply. That’s the same situation with Android: Any mobile handset manufacturer can use it for free. In the long run, it is possible this difference may be what will make Google dominant in the mobile space. Far more consumers may own Android handsets in five years than iOS devices, because the costs are zero for manufacturers to adopt Android. Note I’m not saying I WANT or unequivocally predict that is going to happen. For now, I’m loving my iPhone4 every day and the power it literally puts into my hands. The landscape is changing fast, however, and my sense is that “true” open platforms (Android) may win out because of marketshare over closed, more expensive alternatives like iOS. Time will tell.

What does this announcement from Google about dropping H.264 support in Chrome mean in terms of the future of web video? In the short term, I agree with Charles Arthur: Not much. Flash plugins will continue to play H.264 content in Chrome as well as other web browsers. YouTube will continue to encode to H.264, so iOS devices will keep humming along playing that content. The announcement to watch for, however, is if Google will choose to drop H.264 encoding on YouTube at some point and switch entirely to WebM. I don’t have a clear crystal ball, but the cloudy one at our house seems to suggest this WILL come at some point. Just as we’ve seen Apple drop built-in plugin support in Safari for Adobe Flash web content on new computers it sells (following suit with the decision not to support native Flash playback on ANY iOS devices,) I think Google is taking steps to eventually leverage its power with YouTube and make WebM the defining standard for web video.

From a video producer’s standpoint, and the executive director of Storychasers eyeing our options for creating mobile applications, this makes the future fuzzy. We’ve already got the vast majority of our project video content in the most accessibility-hostile format: Flash. Most of the videos on our COV and CKV learning communities were uploaded directly to Ning and encoded in Flash. As we look at mobile app options like Mobile Roadie, we’d need to develop an automated process (or a manual one) for converting our Flash videos to H.264. Skyfire Rocket may be an option, but it’s not clear to me they have as scalable and flexible a solution / CMS as Mobile Roadie. Perhaps uploading content or cross-posting to YouTube now will hedge our bets, resulting in available formats in both H.264 and WebM? I’m not sure but I’d like to know. If you have thoughts on this or other points / ideas raised in this post, please chime in with a comment!

What will Blip.tv do in the wake of this WebM / Chrome announcement? Maybe nothing in the short term, but long term I’d expect them to offer transcoding to WebM as another video “target” option for Pro users. If you’re not familiar with Blip and are interested in web video, you definitely should subscribe to their official blog. Blip is poised to help content producers revolutionize the video delivery landscape, and is already making important inroads. The following interview from December 2010 with Blip.tv co-founder and CTO, Justin Day, gives some good background on where IPTV is currently and what the future holds for web shows on the living room televisions of people worldwide. This video was featured in the Streamingmedia.com article, “Blip.tv Replaces Flash with HTML5 Player.”

What can we say with relative confidence? The future will be increasingly mobile and media-rich. We need to learn and help our students learn how to “talk with media” and become storychasers. Will the media we create be in H.264 or WebM format? Yes – Both. At least for now.

Technorati Tags:

apple, google, ios, youtube, html5, open, android, webm, format, codec, flash, blip, microsoft, browser

If you enjoyed this post and found it useful, subscribe to Wes’ free newsletter. Check out Wes’ video tutorial library, “Playing with Media.” Information about more ways to learn with Dr. Wesley Fryer are available on wesfryer.com/after.

On this day..

- Remember TEACHERS Make the Biggest Difference, Not Devices – 2012

- Teacher Leader Effectiveness (TLE) and the Tulsa Model #oaesp12 – 2012

- More iPhone Videography Success with ReelDirector – 2011

- Week 2 Lecturecasting with Ustream, Blip.tv and MPEGstreamclip – 2010

- Watch and Read Citizen Journalist Reports from the Inauguration Tuesday – 2009

- Spam on the rise – 2007

- Southwest digital storytelling contest – 2007

- Thoughts on digital discipline – 2007

- Gifts from Christopher Paolini – 2007

Comments

One response to “Browser Wars and Codecs: WebM, H.264, Flash, Silverlight and the Future of Web Video”

Hi Wes,

Great article – well-written, well-researched; everything writing on the web should be. I would, however, like to point out that while you are indeed correct that both Apple and Google are desperately vying for control over video and Apple is certainly pushing their own agenda and dancing with language as the situation dictates – Google is far from an angel in this campaign, trumpeting “open” as though it were synonymous with “freedom.”

It isn’t.

In fact, I suspect this electric circus is a bit misleading. Let’s peel back a layer and probe another perspective. I posit we should more closely evaluate copyright law in the country, now somewhat antiquated in our brave, new, digital world. The copyrights surrounding these compression/decompression (codec) algorithms need much revised scrutiny. For instance, MPEG-LA is carefully evaluating WebM and VP8 for potential lawsuits as discussed in this article at All Things Digital: https://digitaldaily.allthingsd.com/20100520/googles-royalty-free-webm-video-may-not-be-royalty-free-for-long/

This coupled with the sad fact that Chrome truly has a thin user base (which is mostly composed of Firefox and Internet Explorer [yeah, it hurts when I write that]), I see this entire affair as colored lights and glamour, digital theater, amounting to little.

Unfortunately, the players will wage war on one another using the press and then, ultimately, the patents they hold in their arsenal once physical and digital ink proves to be too little or their fickle users choose one or the other.

But the system in which they operate, they manipulate to their gain, deserves a closer look, don’t you think?

After all, boys will be boys – until somebody calls their lawyer.

DISCLAIMER: I use both Apple products AND Google products. I like them both for completely different reasons; but I pledge allegiance to neither. Both have shown their willingness to obfuscate or even murder the truth to protect and advance their respective agendas.